Killing to Keep - Violent Field Practices and Natural History in the Age of Empire

The Project

As the consequences of the Anthropocene become one of the most pressing political issues of our time, humans are beginning to grapple with their destructive relationship to nonhuman life. What does it mean, for example, to kill animals in order to study them? A historical exploration of violent humanistic knowledge practices in the age of Empire.

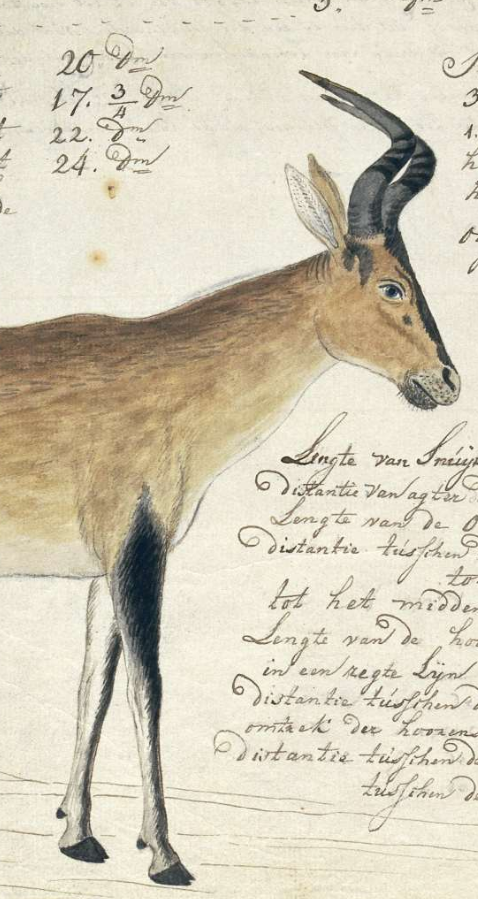

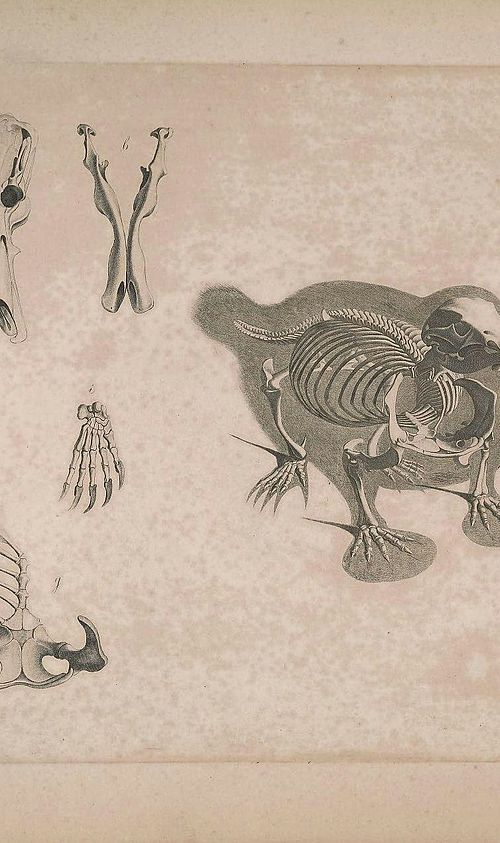

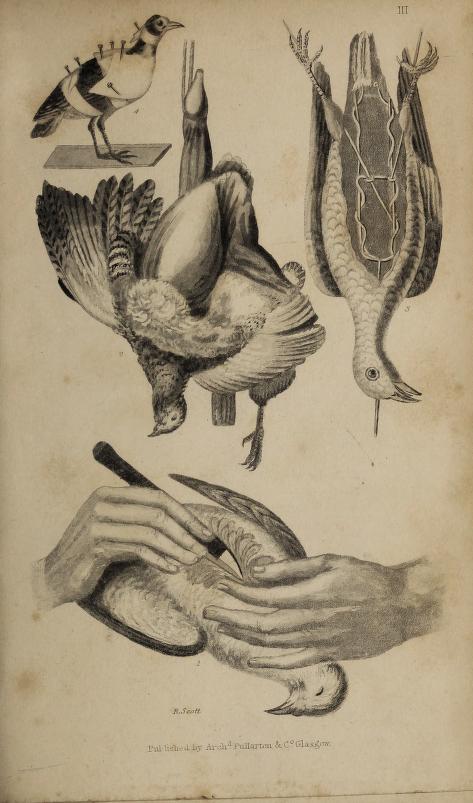

In the nineteenth century, conquering the world also meant exploring and mastering it scientifically. This project follows those men and women who travelled around the globe to collect animals in order to study them. The fact that “collecting” actually meant to capture and kill specimens by the hundreds and thousands, and that this violent work had to be organized and performed by somebody, is a part of modern scientific practice that has yet to be carefully scrutinized and historicized.

The project looks at three different collecting grounds:

- Birds in the tropical dry and moist forests of northern Latin America

- Fish and mollusks in the shallow and deep waters of the South Pacific

- Large mammals in the mixed wood and grasslands of southern Africa

- A forth focus of the project examines the objects themselves, i.e the animal specimens, and the museums that house them today.

Our goal is to account for the complexities of human curiosity and the many different and culturally specific histories of violence against nonhuman and human life within the broader framework of colonial subjugation and its politics of difference - in order to write the history of Humanism as a posthumanist history of imperialism.

Subprojects

News

The Team