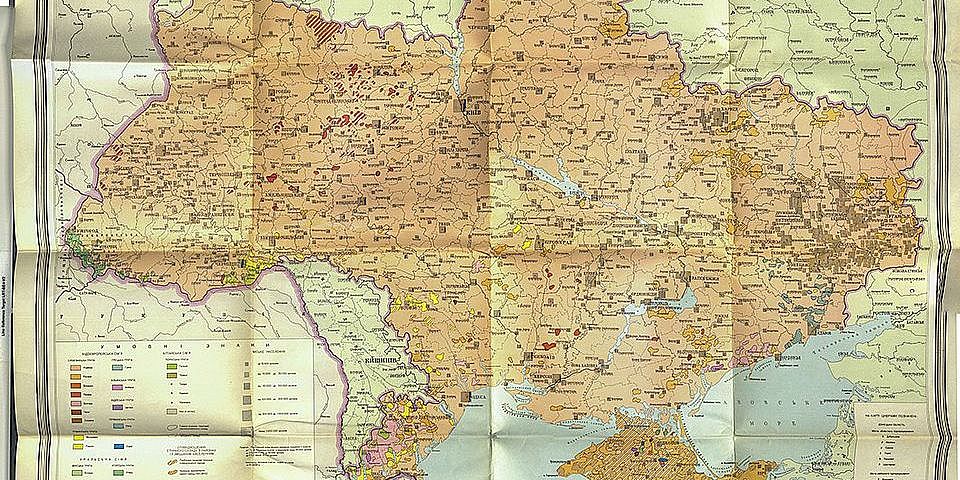

My dissertation is part of the SNSF-Prima research project, "Red Tower of Babel: Soviet Minorities Experiment in Interwar Ukraine," under the supervision of Prof. Dr. Olena Palko at the University of Basel. This research delves into the dynamics of nationality and minority policies in post-Stalinist Soviet Ukraine. By comparing the regions of Transcarpathia and Lviv Oblast—both located on the western border yet marked by significant differences—the project uncovers specific nuances and commonalities that are essential to understanding local conditions.

In the Soviet Union, every citizen was categorized by nationality (ethnicity), a fundamental marker for population management. However, following the affirmative nationality policy of korenizatsiia, a unified nationalities policy ceased to function as a comprehensive program after the early 1930s. The dismantling of institutional structures that once protected minority rights effectively rendered these groups invisible. To borrow Yuri Slezkine's famous metaphor, there was no longer a place in the Soviet Union's Kommunalka for those whose nationality lacked its own titular territorial entity. Subsequent Soviet policies toward nationalities and minorities became selective, unbalanced, and inconsistent, with decisions driven by individual factors rather than coherent guidelines on nationality.

Proclaimed goals like sblizhenie (rapprochement) and sliiane (merging), aimed at creating a unified Soviet people were more idealized descriptions than actionable policies. While the Soviet state set an assimilative imperative in principle and repressed national cultural expressions, the degree of discrimination and oppression varied among different national categories, depending on various factors. In this policy vacuum, lacking a precise plan of action, people found space to negotiate. Local religious and cultural elites, alongside ordinary individuals, adeptly navigated Soviet policies, negotiating freedoms and conditions based on their specific contexts. They often leveraged support from internal actors, such as cultural or religious organizations, and external actors, including kin-states or other patrons.

Individuals, along with local religious and cultural elites, adeptly navigated the policies implemented by authorities, negotiating freedoms and conditions based on contextual nuances. The responses of minorities to the assimilation imperative were shaped by various factors, leading to the adoption of diverse strategies. Identity, while significant, plays a subsidiary role; instead, it is the public and official treatment of individuals within framed groups that dictates the (positive or negative) discrimination and resulting social inequalities. Through this lens, I endeavor to underscore that the Soviet Union's nationality policy was not solely determined by state structures but also influenced by individuals within these frameworks who exercised agency.

The project challenges the notion of a consistent Soviet nationalities policy, arguing that the treatment of minorities was shaped by a variety of factors, including local peculiarities and international pressures. In this environment of policy ambiguity, minority groups seized opportunities to negotiate their rights, drawing on both internal support and external advocacy. By juxtaposing the experiences of different minorities in Transcarpathia and Lviv, the study seeks to offer a more inclusive and multinational perspective on Ukrainian history.

First supervisor: Prof. Dr. Olena Palko (Basel)

Second supervisor: Prof. Dr. F. Benjamin Schenk (Basel)

Third supervisor: Prof. Dr. Krista A. Goff (Miami)