“What’s God got to do with it?” At the end of our journey in the footsteps of the Basel Mission, the answer to this question – the title of one of our preparatory seminars – was clear: Quite a lot, whatever you may or may not think of Him.

In the first week of July 2024, students and instructors from the University of Basel, the Akrofi-Christaller Institute (ACI), and the University of Ghana (UG) participated in an excursion in Basel and southern Germany. This journey, which followed a first that took place in Ghana in early 2024, allowed participants to experience and assess how the historical legacies of the BM are presently perceived, preserved, and presented in Europe.

With over 30 participants, the group experience was enriched by sharing across diverse cultural and generational backgrounds. These exchanges taught us many lessons: for one, sometimes positionalities tied to one’s geographical/cultural origin do not always restrict shared opinions with people from a different place. What one believes in, or whether one holds any religious belief at all, definitely matters in how we assess mission history. Another prominent lesson, particularly for the Basel-based participants was this: A cultural shock at home can hit you just as hard as a cultural shock abroad.

We started our programme on the premises of the Basel Mission house with a tour guided by Claudia Buess and Alexandra Flury-Schölch. From Missionsstrasse, we walked through Basel city along the route of Mission 21’s curated tour called “Mission and Colonialism” which illuminated the entanglements between the mission’s (and Basel’s) history and imperialism. Such entanglements included, among many other things, aspects of trade and slavery, the exhibition of different “peoples” in the Basel zoo (Völkerschauen) as well as the history of Anjama, a woman of noble birth who left her hometown in southern Ghana to join a missionary family on their way back to Basel.

Our excursion programme then took us to the Stuttgart region, where we visited towns known for their strong historical roots in the pietism movement. In Gerlingen, the place of birth of prominent Basel missionary Johannes Zimmermann, archivist Klaus Herrmann had prepared a packed programme for us, which included a visit to Zimmermann’s former home and the local museum, where Mr. Sellner guided us through a small but exciting collection of artefacts that show the tangible relationship between Gerlingen and places where the town’s kinsmen went to spread Christianity. Johannes Zimmermann’s life in Ghana was prominently staged in a thatch-roofed shed with personal objects including a traditional stool he used when he sat in the council of advisors in the king’s court in Kroboland. As we learned in detail from former mayor Alfred Sellner, in the past few decades, there have been several exchanges between Gerlingen and Kroboland, celebrating the historical bonds between these places initiated by the Basel Mission.

In neighboring Korntal, Klaus Andersen, the former head of the Korntal congregation (Brüdergemeinde), introduced the town as an exemplar of a self-sufficient 19th-century pietist settlement, sustained by farming, a wine press, and a food bank. Mr. Anderson also highlighted how Gottlieb Wilhelm Hoffmann, the founder of Korntal, envisioned a settlement guided by the reformist teaching of Martin Luther, which translated into devout Christian everyday living and symbolism. Many participants were reminded of towns like Abokobi and Akropong in Ghana, where missionary founding figures like Hoffmann or Zimmermann also loomed large in local memory culture.

On the fourth day, one part of our group hiked to Mount Chrischona in Riehen, another prominent site of pietistic missionary training in the 19th century. We briefly looked into the history of Cornelius Badu, born in 1847 in Elmina (Ghana), who spent some time in missionary training at Mount Chrischona, but throughout his life according to historian Paul Grant struggled to play the role of the “grateful African convert”.

Our programme also included two half-days in the Basel Mission archive, with our Ghanaian guests working on their own research themes while Basel-based students assisted them with their German language skills. The small archival staff, Andrea Rhyn and Patrick Moser, did their utmost to cater to the needs of our guests, realizing that for many, this visit to the “mother archive” was long-anticipated and of great importance.

Echoing similar activities during the Ghana excursion in January, we also had the chance to speak to descendants of Basel missionaries. In an eye-opening conversation, three members from the children’s/grandchildren’s generation shared their very personal encounters with the heritage of the Basel Mission, having been raised in the tradition of pietist discipline, experienced separation from their parents and/or suffered under their isolation from local children in both Basel and Ghana.

Thanks to the efforts of the Museum der Kulturen staff and curators, participants were offered unique insights into the museum’s depot to look at items collected by former Basel missionaries in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Our Basel-based participants could not do anything with these foreign objects, which Basel missionaries had classified under the nebulous and condescending term of “fetish”. However, many of our Ghanaian guests had rather clear ideas of what these objects had been used for and what they meant to their previous owners.

The excursion ended with an in-depth evaluation by groups of our students of the freshly published source collection, The Reports of Theophilus Opoku: A 19th Century-Gold Coast Pastor (2024) edited by anthropologist Michelle Gilbert and historian Paul Jenkins. During the discussions, many crucial topics were raised, spanning Opoku’s hotly debated “derivative” language and tone as a Ghanaian collogue. The discussions were followed by the eventful launch of the volume punctuated by a memorable cocoa pod-breaking ceremony by Leonard O. Agyemang and Adelle A’asante. Good-byes were stretched out over a concluding reception dinner, a church service, and a farewell lunch in subsequent days.

The output of the excursion is currently being curated into short blog posts for display on a website (baselfo.ch, under construction), which will host individual and collaborative works produced by students.

Our excursions have been timely in many ways. First, they reinvigorated interest—critical and clerical—in the Basel Mission’s history ahead of the 2028 bicentenary anniversary of the mission’s first arrival in Ghana. Secondly, we have built new networks amongst individuals and institutions in Ghana, Switzerland, and Germany from which fruitful collaborations are underway (e.g., exchanges of archival materials between the mission archives in Basel and their counterparts at ACI). Thirdly, the forthcoming website will not only deepen the scholarship on the Basel Mission but also provide a medium for continued engagement among the partner institutions.

Finally, this exchange has shown how rewarding it can be to draw practical lessons from postcolonial criticism – especially at a time when “postcolonial” has become a discursive trigger in some circles. However, we also came to understand that an unquestioned right to question and critique whatever one pleases, including an individual’s religious beliefs and heritage (even if by implication), can be just as narrow-minded as the religious zeal of the first Basel missionaries.

Special thanks to Veit Arlt (Center for African Studies Basel) and Andrina Sommer (History Department, Basel); Samuel Bachman, Ursula Regehr, and Isabella Bozsa (Museum der Kulturen, Basel); Claudia Buess, and Alexandra Flury-Schölch (Mission 21); Patrick Moser and Andrea Rhyn (Basel Mission archives); Klaus Herrmann and Klaus Andersen and everyone else who contributed to our visits to Gerlingen and Korntal; Hannes Kölle, Beate Saalmüller and Monika Messerli, as well as Frederick Gyamfi Mensah (Uni Basel) for their support to make this excursion successful.

Text: Ernest Sewordor, Julia Tischler

What’s God got to do with it? This was the question posed in the title of a preparatory seminar that Basel- and Ghana-based students took before participating in an excursion that interrogated the heritage and legacies of the Basel Mission (BM) in southern Ghana.

The excursion was the first of two parts, jointly organized by the University of Basel, the Akrofi-Christaller Institute (ACI), and the University of Ghana (UG). It took place on 16–23 January 2024 and included 20 multinational students and 5 instructors. In summer, our Ghanaian colleagues will visit Switzerland and southern Germany for a similar event.

Basel’s missionary relationship with Ghana dates to 1828, when the first four Europeans sent by the BM landed on the Gold Coast (present-day Ghana) at the invitation of the Danish colonial governor resident in Fort Christiansborg. So, naturally, the landing site was where we started our excursion guided by Professor Nii-Adziri Wellington, a Ghanaian heritage scholar and architect. Prof. Wellington walked us through the nook and cranny of Osu, a town adjoining the fort to retrace the material (and imagined) remains of the BM by highlighting an erstwhile trading post, commemorative tombstone epitaphs, cemeteries, and the spatial impact of the British bombardment of Osu in 1854 when the locals refused to pay a colonial tax.

On the second day, the students split up into groups to conduct research in Ghana’s national archives and the Balme Library on UG’s Legon campus, following their individual research interests, which they had already developed during the preparatory seminar. Some also went back to Osu to interview schoolteachers, children, and church elders associated with the Presbyterian community, the successor church of the BM.

On our third day, we visited Abokobi—a town the Basel missionaries established and settled after the 1854 bombardment, situated about 15 miles north of Osu. The group that first arrived in Abokobi was led by German-born missionary Johannes Zimmermann alongside African catechists-in-training, servants, and converts. Thus, it is not surprising that the Abokobi church is named after Zimmermann—who is celebrated with a bust erected in his honor in a place named Zimmermann Gardens, where he is believed to have originally translated the bible into the Gã language. While European missionaries like Zimmermann received the praise it took questions from our group for Rev. Samuel Sowah, the deputy minister of the Abokobi congregation and our tour guide, to highlight the fact that Africans (known or not) contributed to the evangelizing work of the BM. For instance, one prominent actor was Paolo Mohenu—a Gã-born traditional priest and herbalist who originally frustrated the work of the missionaries but later converted to Christianity and became one of the Mission’s most influential evangelists. Abokobi is a small settlement but an impressive one. A variety of heritage moments—including a Heritage Square, original tombs of European missionaries and African evangelists, and a particular architectural style for some buildings document the town’s historical significance.

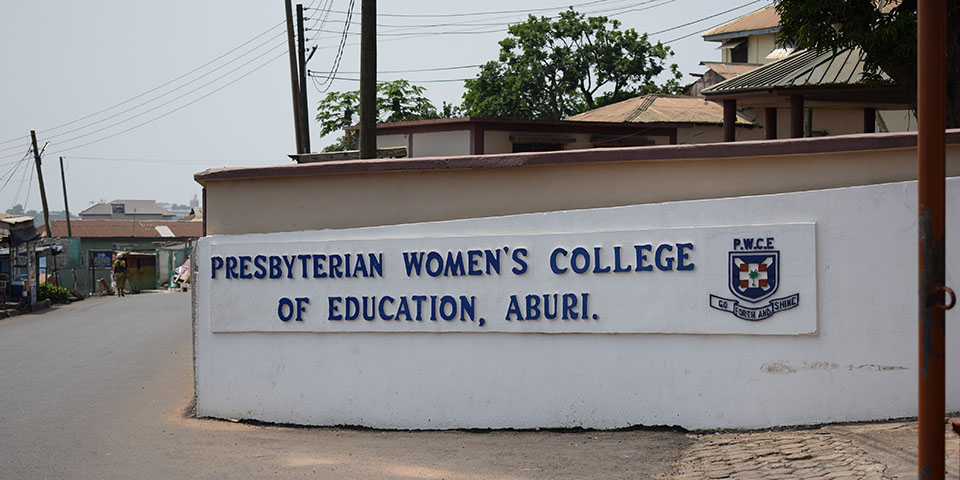

The next phase of our excursion focused on Akropong, the capital of the Akuapem kingdom in the Eastern Region of Ghana. We spent two days exploring remnants of the BM’s presence in the town through walking tours, oral interviews, and archival work at the ACI library. We visited the graves of the earliest European missionaries. We were also welcomed at several ancestral households of some influential BM-trained African and Jamaican pastors (e.g., Theophilus Opoku, David Asante, John Hall, and Peter Hall) and interviewed their descendants, who generously shared information about the contributions of their forebearers to the BM in Ghana. Furthermore, we were warmly received when we attended a service at the Christ Presbyterian Church (formerly Basel Mission Church) and were granted an audience at the palace of Krontihene Boafo Ansah III, the senior divisional chief of Akropong. Here and on numerous other occasions, we witnessed the many ways in which Christianity and so-called traditional (spi)ritual life coexist. During a closing workshop at UG’s Legon campus, students presented the progress they had made with their individual research topics, including the notion of discipline with BM/Presbyterian education, the contribution of missionary-physicians to medicine, the commercialization of cocoa production, slavery, the materiality of heritage, and the intersection between Christianized chieftaincy and gender in Ghana.

Our excursion taught us many things, not the least that the Basel Mission means different things to different people. “To you [Europeans], Basel is a city, but to us [Ghanaians], Basel is a church”, as the Rt. Rev. Dr. Abraham N.O. Kwakye, head of the Presbyterian Church of Ghana and prominent Basel Mission historian, told the excursion group during a dinner at his official residence. The BM was founded to — in the eyes of its supporters — propagate the gospel of God, but it was an institution run from Basel by white men with specific 19th-century colonial and racist worldviews. Indeed, we often heard critical comments about the BM’s disregard for local knowledge and cultural practices. At the same time, Basel-based students were struck by the often positive ways in which Ghanaian interlocutors addressed the missionary legacy. For many, “Basle” (or Basel) remains an affectionate aphorism that denotes Christian discipline and honest work ethics, and an integral part of their cultural and religious identity. As we learned in Ghana, the BM story is a shared experience consisting of negotiated encounters. Both troubling discourses and actions as well as positive assessments of the BM’s impact on education and health, among others, can serve as departing points to ask new questions that facilitate a critical reassessment of the historical encounters between European BM pietists who crossed the Atlantic Ocean to spread the message of Christ and their African counterparts in the past and present.

Reciprocity, equity, and transparency were the pillars on which our collaboration was built. Despite the fact that the institutions involved in the collaboration were unequally resourced partners and despite visible differences in privilege among participants (not least financial), all participants were open to share and learn across unfamiliar cultures and discuss difficult topics like religion, slavery, gender, and patriarchy with sensitivity and respect. At times when certain sections of the media discredit postcolonial theory, this was a living example of what can be gained by approaching teaching from such a perspective.

Text: Ernest Sewordor, Julia Tischler