/ Forschung / Yonatan Duran Maturana

Keyeme: The Spirit Guardian of the Amazon Basin Animals

Ethnographic sources on Indigenous societies of the Amazon basin reveal to a greater extent than scientific expedition reports or animal collections the anthropological and ecological universe of these societies, as well as their relationships with nature.

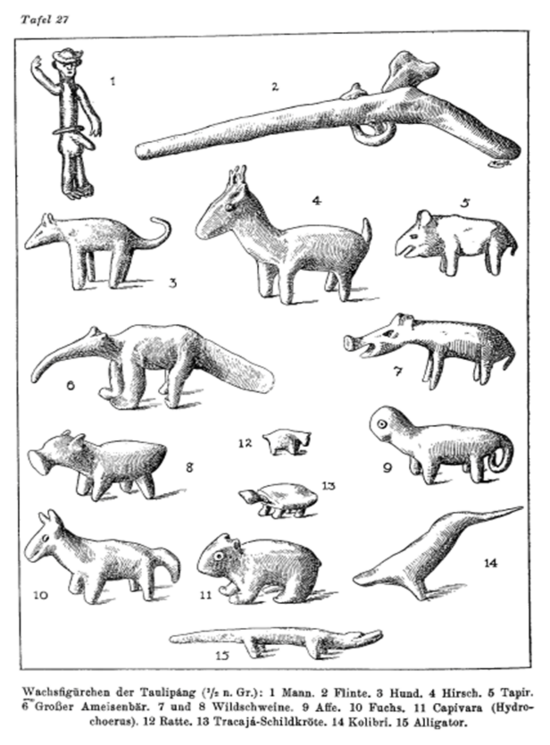

In the early twentieth century, the Königliches Museum für Völkerkunde in Berlin—the present-day Ethnologische Museum, part of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin—sent the German ethnologist Theodor Koch-Grünberg (1872–1924) on an ambitious journey through northern South America. Between 1903 and 1905 he explored the Yapura and the Rio Negro on the Venezuelan border, carefully documenting Indigenous life and collecting artifacts—of which approximately 1,252 are preserved in the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. His work was later published as Zwei Jahre unter den Indianern: Reisen in Nordwest-Brasilien, 1903–1905 (1909-10).

A few years later, in 1911, he returned for a second expedition, this time traveling from Manaus up the Rio Branco to Mount Roraima in Venezuela. There, he recorded myths and legends of the Pemon—Indigenous people living in areas of Venezuela, Brazil, and Guyana—, whom he identified as Arekuna, Kamarakoto, and Taulipang. These stories were published in five volumes under the title Vom Roroima zum Orinoco: Ergebnisse einer Reise in Nordbrasilien und Venezuela in den Jahren 1911–1913 (1917).

On these journeys, Koch-Grünberg did more than collect artifacts—he opened a window into the spiritual world of Amazonian societies. One of the themes that fascinated him most was the relationship between people and animals, especially through hunting. Years before his travels, the Brazilian explorer João Barbosa Rodrigues (1842-1909) had also described similar traditions in his Poranduba Amazonense (1890). Both were struck by a recurring idea among Indigenous hunters: the belief in a “master of the animals,” a spirit guardian who protects creatures of the forest and decides how many may be taken by hunters. This figure often appeared as a human-like being, but just as often took the shape of an animal, capable of shifting forms at will. For instance, among the Taulipang, this spirit was known as Keyeme, a gigantic water serpent: “He is like a man,” say the indigenous people, “but when he puts on his colored skin, he turns into a great water serpent and becomes very evil.” (Koch-Grünberg, 1917, p.177).

According to local myths, Keyeme was punished by the birds for dragging every living thing down into the depths. Once he was defeated, his shimmering, multicolored skin was torn apart and distributed among the birds and other animals. From that moment on, each species carried its own unique plumage, skin pattern, and voice. In this way, Keyeme became remembered above all as the master of the birds. The story is more than a tale—it reflects a widespread Amazonian belief that spiritual beings gave animals their distinctive colors and sounds. For the Taulipang, Keyeme was not just a monster, but a man who transformed into a serpent whenever he wore his magical skin.

But Keyeme’s role went beyond myth. He was also the one who guided prey toward hunters and judged their behavior. If hunting was done with moderation and respect, Keyeme would favor them; if it was done carelessly or greedily, he would punish them. For this reason, indiscriminate hunting was a taboo, and rituals such as offerings or prayers were essential before and after each hunt. Bird hunting was not a casual act. It was regulated by spiritual rules, because birds were tied to stories of creation and survival. This balance was shattered in mid-nineteenth century, when large-scale hunting for trade and science entered the Amazon.

Birds held a special place in the imagination of Amazonian peoples. Some myths say they brought humanity essential gifts such as fire or fertility. In others, they guided the souls of the dead to the afterlife. Killing a bird was therefore never trivial. It required gestures of reconciliation: words of forgiveness, offerings of chicha, or carefully laying the animal’s body on leaves so that its spirit would be honored and the continuity of hunting secured (Koch-Grünberg, 1917).

Even the hunting tools themselves carried symbolic meaning. The blowgun, for instance, was more than just a weapon: it was seen as a kind of umbilical cord linking the hunter to the forest and its invisible guardians (Taylor, 1996). Its darts, tipped with curare poison, allowed hunters to reach birds perched in the highest canopy. Bows, arrows, and traps completed the set of techniques. Yet what truly mattered was not the efficiency of the weapon but the balance of the ritual that surrounded every shot.

Ethnographic sources, such as Rodrigues and Koch-Grünberg, remind and teach us that hunting was never just about survival—in terms of subsistence and nutrition. It had—and still has—a central anthropological dimension, in which the dialogue with the forest, a negotiation with its spirits, and a way of maintaining harmony with the world of animals were important aspects of that practice. In the feathers of a bird or the shape of a blowgun, one could glimpse not only food or tools but a profound vision of life in which humans, animals, and spirits shared a common destiny. In this sense, hunting birds is an expression of specific anthropological relations.

Sources

Koch-Grünberg, Theodor. Vom Roroima zum Orinoco: Ergebnisse einer Reise in Nordbrasilien und Venezuela in den Jahren 1911–1913. 5 vols. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer, 1917–1928.

Rodrigues, João Barbosa. Poranduba amazonense, ou kochiyma-uara porandub, 1872-1887. Rio de Janeiro: Typ. de G. Leuzinger & Filhos, 1890.

Taylor, Anne-Christine. “The Soul’s Body and Its States: An Amazonian Perspective on the Nature of Being Human.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 2, no. 2 (1996): 201–216.