/ Forschung / Prof. Dr. Marie Muschalek

Hippo Teeth in the Archive

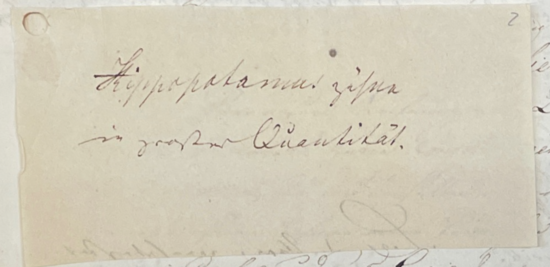

One time, when working in the archives in Berlin, I stumbled upon an mysterious note that read “Hippopotamus teeth in large quantity.”

Earlier this year, I was doing research in the archives of the Natural History Museum in Berlin, the Museum für Naturkunde, I opened a file holding the museum’s correspondence with one of its collectors, and the very first document that greeted me was a small cut-out piece of paper, about twelve by five centimeters large, onto which someone had written in old German handwriting: “Hippopotamus teeth in large quantity.” Now what was this about, I asked myself. And why had it been cut out of a larger document and then later archived separately? Someone had thought this information about the contents of a consignment sent to Berlin important enough to separate the passage from the initial letter or list.

The archival file in question pertains to a Prussian collector named Karl Heinrich Bergius who, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, travelled to the Cape Colony to gather botanical and zoological specimens for the Museum in Berlin and other public and private buyers. Recommended by Hinrich Lichtenstein, the director of the Berlin Museum, Bergius, a pharmacist by training, had found employment with Pallas & Poleman, a pharmacy in Cape Town. On his days off, he pursued his collecting trade. His file of correspondences with Lichtenstein is rather short – as was his time at the Cape. Having arrived there in 1815, age 24, he died of tuberculosis only three years later, in early 1818. His letters reveal an initial enthusiasm, a strong passion for botany and orchids in particular, but then later on, slip into complaints about his bad working conditions, his dire financial situation, and his deteriorating health. Because Bergius’ means were limited, his collecting hauls took him only into the nearby areas of the Table Mountain and the Cape’s coast, and he concentrated on rather small specimens – seeds, insects, birds, small mammals. There is no reference to a hippopotamus hunt in his correspondence with Lichtenstein. There are several detailed descriptions of hippopotami and hippo hunts in the Dutch officer and explorer Robert Jacob Gordon’s writings, though, from which I took the two drawings you can see in this post. I will have to write about Gordon’s journals in another blog post. How a large number of this large, thick-skinned semiaquatic African mammal’s tusks would have ended up in one of Bergius’ consignments and then made it into an archival note in the Berlin Natural History must remain a mystery. My suspicion is that he had bought, received, or taken the tusks from others – black or white hunters or traders maybe. The scientific value of hippo teeth was fairly limited without the skull, skeleton, and skin. But Bergius (or someone in the museum) must have known that on the ivory market they would fetch a good price – almost as high as elephant tusks. His patron institution in Berlin, in any case, did buy and sell natural objects on the global naturalia market in order to generate revenu, from which he would also have benefited. Hence, it is possibly the market value of ivory that explains the cut-out note that I recently stumbled across.

My subproject within the larger research project Killing to Keep focuses on the practices of violence involved in collecting animal specimens from southern Africa for natural history museums in the early nineteenth century. My approach is micro-historical: I am particularly interested in the minute hand gestures, daily routines, techniques and tools collectors deployed in their hunts for zoological objects. How, for instance, did Bergius get his hands on hippopotamus tusks? Who – indigenous and intruders alike – was involved in the hunt and how, with what kinds of weapons and techniques, did they kill this fierce animal? How long did it take them? What were they feeling, what were they thinking? How easy or difficult (both physically and emotionally speaking) was it? What did they know or hoped to get to know about the animal they killed? I wish to connect these questions and observations about the small, mundane, and quotidian to larger frameworks – to natural knowledge regimes and animal cosmologies, to the aforementioned specimen trade, to different hunting cultures, and most importantly, to the violent context of colonial subjugation – and thus push our understanding of how micro-gestures of violence related to broader developments of Humanist knowledge production in the age of Empire.

The collection managers at the Berlin Natural History Museum will know if there are indeed large quantities of hippopotamus tusks in their storage facilities, and if so, maybe also where they came from. I need to ask them. Also, if they know how much the tusks were worth. And I need to learn more about the ivory trade and hunting practices in southern Africa at the beginning of the nineteenth century. What I have already learned, however, is that since the arrival of the first European settlers and of enslaved people under the auspices of the Dutch East India Company in the seventeenth century, and with the ensuing inland migration of mostly poor, semi-nomadic pastoralist trekboer families in the eighteenth century, the demographic make-up of the southern tip of Africa had been rapidly shifting, which had also had an impact on its ecology. There is evidence that southern African flora and fauna changed drastically under the human influence of colonization. Settlers started sedentary forms of farming, clearing forests, relying heavily on cattle meat, supplementing their diets with game. With white expansion into the interior, assisted by guns and horses, the hunting frontier was pushed further north and east. In the meantime, animal parts, most notably ivory, but also ostrich feathers and rhino horns, became more and more valued, internationally traded commodities connected to the East African coastal trade network. As a consequence, and starting already at the beginning of the eighteenth century, certain southern African policies (notably the Bantu speaking Venda, Tsonga, and Sotho) specialized in commercializing ivory, to be processed in the Portuguese controlled Delagoa Bay factories and then shipped into the rest of the world.

And thus, when Bergius collected specimens in the Cape in the 1810s, wildlife had already started to thin out. It had been overhunted, displaced by agriculture, and had migrated beyond the plains on the outskirts of Cape Town, towards the Kalahari, the Highveld, and the Orange and Limpopo Rivers.

Literature

Alpers, Edward A. “The Ivory Trade in Africa. An Historical Overview.” In Elephant: The Animal and Its Ivory in African Culture, edited by Doran H. Ross. Fowler Museum of Cultural History, University of California, Los Angeles, 1992.

Beinart, William. “Empire, Hunting and Ecological Change in Southern and Central Africa.” Past and Present 128, no. 1 (1990): 162–86.

Carruthers, Jane. “Romance, Reverence, Research, Rights: Writing about Elephant Hunting and Management in Southern Africa, c.1830s to 2008.” Koedoe 52, no. 1 (2010).

Krüger, Gesine. “History of Hunting.” In Handbook of Historical Animal Studies, edited by Mieke Roscher, André Krebber, and Brett Mizelle. De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110536553-041.

MacKenzie, John. The Empire of Nature. Hunting, Conservation and British Imperialism. Manchester University Press, 1997.

Short, John P. “Global Consciousness, Commodity Form, and the Natural History Object.” Colloquia Germanica 45, no. 3/4 (2012): 280–94.