/ Forschung / Hanna Wüste

The bird that loved potatoes. Memories of a Manumea.

Research into the entangled history of humans and animals rarely follows a straight path. More often, I come across small, seemingly minor stories - details that might be overlooked in broader histories but reveal the heart of the narrative I want to tell. They turn vague ideas into something tangible. One of those stories is about the bird that loved potatoes.

Manumeas are understood to be pigeons, closely related to the Dodo. They have the size of chickens and eat fruits native to the Samoan islands, that cannot be eaten by other birds, using their relatively big read beaks. In 1870 a living Manumea bird from Samoa was taken aboard the «Wandrahm», a ship of the Hamburg trading firm J. C. Godeffroy & Sohn. The Swiss natural history collector Dr. Eduard Graeffe, his wife Maria Rosa Pancol and their son Eduard began their journey back to Hamburg after ten years in Samoa. In his short autobiography[1] Graeffe describes the boredom that soon set in on the long journey home, and mentions one of their distractions: «A living Manu-nua [sic!], Didunculus strigirostris Jard, which had become very tame, seemed to appreciate the attentive care my wife devoted to it with cooing sounds […].» The Manumea was not the only animal taken alive on the «Wandrahm»: «A large Birgus latro crab, which escaped several times by bending apart the iron bars of its cage, amused us with its climbing skills on the masts, but it did not endure captivity for long.»

The bird held on, although it becomes clear that the conditions on the ship were far from ideal for the animal, and only a chance encounter on the high seas ensured its survival: «As we continued our journey, we saw a German ship […] not far from us, following the same course. Since we no longer had any potatoes, the Didunculus' favorite food, on board, the captain [Früchtenicht] approached the ship and asked for potatoes. […] Since we had already despaired of bringing the rare bird alive to Hamburg without potatoes, we were doubly delighted by the encounter with the obliging captain [from Oldenburg].»

The journey continued to Kap Horn, crossing to the Atlantic Ocean, then Montevideo in Uruguay, through the Sargasso Sea, passing Flores of the Azores and finally the lighthouse of Helgoland. Arrived in Hamburg, the bird did not stay with the Graeffe family. «[Johann Cesar Godeffroy] was delighted with the living Didunculus, the first specimen brought alive to Europe, which, much to the chagrin of my wife, who had grown very fond of the bird, was handed over to the zoological garden in Hamburg. Mr. Godeffroy was kind enough to comfort my wife by giving her a gold chain and watch as a gift.»

Today, one can find two specimens of Didunculus strigirostris in the catalogues of the Museum der Natur Hamburg that were collected in 1870, one male and one female.[2] It is not likely, that the bird that loved potatoes is one of them. Index cards confirm that Graeffe was the one sending the two mentioned specimens to Germany in August 1870, three months before he arrived in Hamburg with the living Manumea. The bird that loved potatoes is thus lost in the entanglements of imperial institutions, amidst a mass of living and dead animals that were brought through a global web of trade to Germany in the long 19th century. But it is certain that it never returned to its homeland.

What is meant as only an amusing anecdote in Graeffe’s autobiographical narrative has various dimensions that are fruitful for thinking about Europe’s imperial history, and its responsibility in the age of extinction. On the personal level, Graeffe describes the loss of a companion, of a being that endured the same hardships as the human travellers, at the same time symbolizing its homeland that Graeffe left «with a heavy heart». The loss, that is felt deeply by Graeffe’s wife Maria, happens at the hand of Johann Cesar Godeffroy, who wants to exhibit the bird to the public in Hamburg’s zoo. Here, the bird is stripped of anything and anyone that is able to contextualize it and becomes a symbol of an imagined paradise.

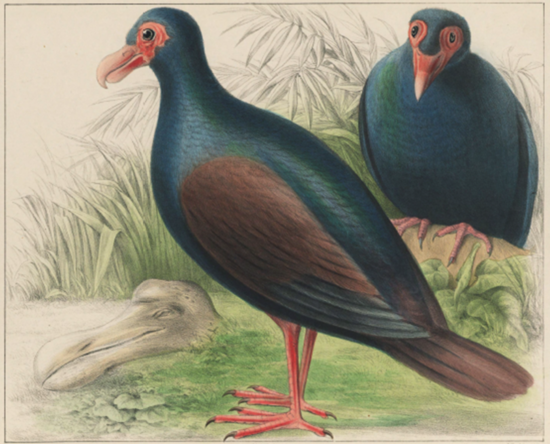

It is the first of its kind, Graeffe writes, to ever reach Europe alive and due to its close relation to the already extinct Dodo, the Manumea also embodies a natural paradise that is retreating. The bird that loved potatoes was in fact not the first living Manumea to reach Europe - the illustration of two Manumeas in Richard Owen’s Memoir on the Dodo published in 1866 was drawn from two birds living in the London zoo.[3] Interestingly, the two birds are shown standing over a deceased Dodo’s «dried head»[4], one of them lowers its beak, maybe in mourning over its lost cousin. It seems a self-fulfilling prophecy to take an animal from its homeland and then create a narrative of natural decline for its display. In the London and Hamburg zoos, for an unknown time, living Manumeas were returning the gaze of a culture that deemed their extinction inevitable.[5]

What would the Memoir of the Manumea say if we knew more about it than its taste for potatoes? Where did it live and who was its living kin? How did it end up in the care of Maria, how long did it survive in the zoo, how did it live there?

Today, the Manumea has become the national bird of Samoa and belongs to the list of critically endangered species, as only an estimated number of between 150 and 200 remain.[6] As the page «Save the Manumea» states: «The Manumea is a key symbol of Samoa's natural heritage and it also helps to protect communities from the impacts of climate change. As a tooth-billed pigeon it uses its large beak to feed on large native seeds that cannot be eaten by other birds. By doing this, it acts as a crucial seed disperser, naturally restoring the native forest.» In 2018, the Guardian reported that illegal hunting threatens the survival of the species further.[7] The bird remains elusive and has not been seen by a human for several years.[8]

By choosing scientific prestige, societal approval and money over the emotional bond and responsibility towards another being, Graeffe and Godeffroy’s exchange showcases the profit-driven mindset of those, who prepared the subsequent colonization of Samoa and other contested territories. Between 1857 and 1879 the Godeffroy firm became the most important land owner of Samoa, cultivating the land with Copra-plantations.[9] The «Wandrahm» did not only bring the Graeffes and the Manumea to Hamburg, it also transported Copra to be sold in Hamburg, as Graeffe recounts: «A storm in the southern part of the South Seas caused the copra stored in the ship's hold to tip over, leaving the ship listing.» One of the reasons the Manumea has become a rare sight on Samoa is deforestation, an obvious continuity to the 19th century cultivation of plantations by the German firm. The index cards of the Hamburg Natural Histroy Museum that record the two Manumeas collected in 1870 also state that they were taken from the Samoan region A’ana, where most of the German plantation land was located due to the fertile soil.

When we contemplate the choices that led the bird that loved potatoes to Hamburg’s zoo, its displacement, the help on the high seas, Godeffroy’s power and Graeffe’s inability to insist on a binding connection to the bird, we might wonder about our own (emotional) distance and proximity to animals. Does fatalism create an emotional bond to otherwise forgotten or discarded collateral damage of human survival and exploitation? Is it possible to mourn animals like the Manumea preemptively? We may even discover our ability to see animals not as doomed victims of our actions but as resilient beings that we force to share the world of our making. They are not simply reacting, they are interacting, sometimes by looking back at us, sometimes by evading our view altogether.

___________

Bibliography

Collar, Nigel J.: Natural history and conservation biology of the tooth-billed pigeon (Didunculus strigirostris): a review, in: Pacific Conservation Biology 21, 2015, p. 186-199. Link

Faasau, Gutu: Manumea remains elusive, Samoa Observer 25 October 2023. Link

Graeffe, Eduard: Meine Biographie in meinem 80. Lebensjahre geschrieben, in: Hans Schinz (Hg.): Vierteljahrsschrift der Naturforschenden Gesellschaft in Zürich. 61/1 u. 2, Zürich 1916, pp. 1–24.

Hance, Jeremy: Caught in the crossfire. Little dodo nears extinction, The Guardian 9 April 2018. Link

Huseynli, Orkhan: Meet The Samoan “Little Dodo” – (Didunculus strigirostris), Unsustainable Magazine 29 January 2024. Link

Meleisea, Malama; Schoeffel, Penelope: Germany in Samoa. Before and After Colonisation, in: Mühlhahn (Ed.): The Cultural Legacy of German Colonial Rule, Berlin / Boston 2017.

Owen, Richard: Memoir on the Dodo, London 1866. Link

Scheps, Birgit: Das verkaufte Museum. Die Südsee-Unternehmungen des Handelshauses Joh. Ces. Godeffroy & Sohn, Hamburg, und die Sammlungen «Museum Godeffroy», Hamburg 2005.

Schmack, Kurt: J.C. Godeffroy & Sohn Kaufleute zu Hamburg. Leistung und Schicksal eines Welthandelshauses, Hamburg 1938.

Footnotes

[1] Eduard Graeffe: Meine Biographie in meinem 80. Lebensjahre geschrieben, in: Hans Schinz (Hg.): Vierteljahrsschrift der Naturforschenden Gesellschaft in Zürich. 61/1 u. 2, Zürich 1916, pp. 1–24.

[2] Catalogue numbers: ZMH-ORN-0013648; ZMH-ORN-0013650 .

[3] The description in Owen’s book reads: «Two views of the Dodlet (Didunculus strigirostris, Peale; Gnathodon, Jardine), natural size, from the living bird, obtained at the Samoan or Navigators' Islands, and transmitted from Sydney, New South Wales, by George Bennett, M.D., F.L.S., to the Gardens of the Zoological Society of London, in 1864, where the paintings, of which the above are facsimiles, were made for the present work. A sketch of the dried head of the Dodo in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, of rather less than half the natural size, is introduced into the picture, now in the Author's possession.»Richard Owen: Memoir on the Dodo, London 1866, p. 51. Link

[4] ibd.

[5] The notion is discussed and contextualized in Nigel J. Collar: Natural history and conservation biology of the tooth-billed pigeon (Didunculus strigirostris): a review, in: Pacific Conservation Biology 21, 2015, p. 186-199. Link

[6] Orkhan Huseynli: Meet The Samoan “Little Dodo” – (Didunculus strigirostris), Unsustainable Magazine 29 January 2024. Link

[7] Jeremy Hance: Caught in the crossfire. Little dodo nears extinction, The Guardian 9 April 2018. Link

[8] Gutu Faasau: Manumea remains elusive, Samoa Observer 25 October 2023. Link

[9] About Godeffroy on Samoa, for example: Kurt Schmack: J.C. Godeffroy & Sohn Kaufleute zu Hamburg. Leistung und Schicksal eines Welthandelshauses, Hamburg 1938; Birgit Scheps: Das verkaufte Museum. Die Südsee-Unternehmungen des Handelshauses Joh. Ces. Godeffroy & Sohn, Hamburg, und die Sammlungen «Museum Godeffroy», Hamburg 2005; Malama Meleisea and Penelope Schoeffel: Germany in Samoa. Before and After Colonisation, in: Mühlhahn (Ed.): The Cultural Legacy of German Colonial Rule, Berlin / Boston 2017.