/ Forschung / Dr. Marie-Charlotte Lamy

Empress Joséphine and the Last Emus

Did you know Empress Joséphine lived with the very last survivors of extinct Australian bird species?

The “dwarf emu”, smaller and darker than the common emu, has been extinct since 1822. The last individuals recorded by scientists lived at the Château de Malmaison, the imperial residence of Joséphine de Beauharnais (also known as Napoleon’s wife), before being transferred to the National Museum of Natural History in the heart of Paris, where they died in 1822. The story of these birds is well known to two groups of people: Joséphine’s historians and ornithologists. And now, you.

I want to share this story with you, because, let’s admit it, it is one of those quirky fun facts we secretly love. But also because it is an excellent example of how history and science can meet at a crossroads to shed light on our neighbours, the non-human animals.

The first question we may ask: how did Joséphine end up with these birds? Well, she established a princely menagerie at Malmaison in 1800, where she kept several animals of many species and origins. To get them, Joséphine used some of her relations, such as colonial governors, but mostly professors from the National Museum of Natural History, an institution created in 1793 to which a public menagerie was attached a year later. These professors were in contact with, among others, explorers who brought back living animals from their voyages of “discovery”. One of the best-known is Nicolas Baudin’s expedition to New Holland – today’s Australia – from 1800 to 1804, as it was the first expedition to return with a good amount of living animals. The zoologist François Péron, with the help of his friend Charles-Alexandre Lesueur, who fashioned himself as a painter, brought back 73 living animals to France. Among them were two emus. After a courteous negotiation between Joséphine and the professors to decide which menagerie the different animals should go to, the emus, with black swans, kangaroos and other animals, ended up at Jo’s in 1804 (Full disclosure: I did my PhD thesis on Joséphine’s menagerie so, yes, after all these years I have come to call her Jo – or Jojo when I am in a very good mood).

The trajectory of these birds is quite “easy” to trace. The Museum’s archives and travellers’ reports allow us to reconstruct the narrative of the animals (and also reveal the terrible conditions of transport and captivity, but I will spare you the details). What I want to highlight here is a difference in perspective: while historians often ask – as I did – how the birds arrived in France, scientists instead ask where exactly they came from. To conduct this investigation, another kind of material is used.

A few months after their arrival at Malmaison, the birds were donated to the Muséum (Classic Jo: she did not hesitate to share “her” animals with naturalists when they had a scientific value). The birds lived there until 1822, and when they died, taxidermists prepared them. Their skins and skeletons are still preciously preserved, considered extremely rare, even unique, as they are the holotypes of the species. Why is that? Because the only specimens preserved of dwarf emus are those brought back from the Baudin expedition (they were five, but only two survived the journey and the other three were taxidermized on board). As for the others, they disappeared in the wild in the early 1800s.

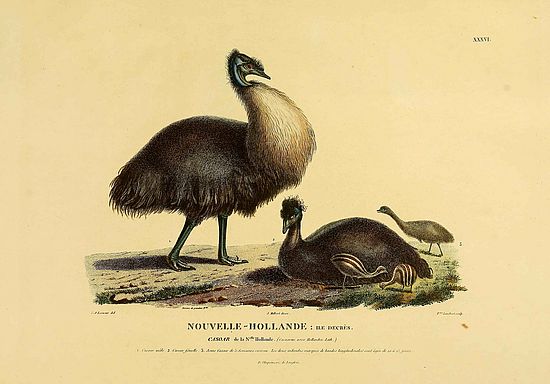

These materials are very important to retrace the origin of the birds, besides the written sources, which scientists also used. But the archives can be tricky. Indeed, it is quite a feat to understand the naturalists of the time and to know which ones can be trusted (apparently, Péron was talking nonsense). Also, the nomenclature changed over time. So, the dwarf emu was vaguely called Casuarius novae Hollandiae in 1804, as in the illustration of Lesueur. Then came decades of refinement, studying anatomy, comparing bones, making paleoethological surveys on sites, taking radioscopies, etc. Progressively, the picture became clearer. In 1817, Louis-Pierre Vieillot discovered that these animals, that were from the islands, were different from the ones living on the mainland. He called them Dromaius ater (and Dromaius novaehollandiae for the species on the mainland). A century later, in 1906, Walter Baldwin Spencer proposed the name Dromaius minor, and established that this species was from King Island. In 1959, Christian Jouanin started to wonder whether the birds were not from one species, but two. And finally, in 1984, Shane Parker found out that one of the emus was from King Island and the other one from Kangaroo Island, giving it the name of Dromaius baudinianus.

So yes, Joséphine unknowingly lived with the very last individuals of not just one species, but two. Meanwhile, the British settlers, who had established themselves a few years earlier on King and Kangaroo Islands, made the two species disappear by 1805, by hunting them with dogs – an extremely efficient killing technique. Contemporary reports confirm that this rapid overhunting led directly to the extinction of both island species.

It is kind of a strange story, if we think about it. The European settlers caused the extinction of two bird species (which actually happened quite a lot since Columbus and the European urge to possess all the lands of the world, a phenomenon commonly known as the Sixth Extinction). But ironically, the captivity structure of Malmaison and the Muséum allowed two individuals to survive for almost twenty years longer than their wild fellows. It is a paradox for sure, but also a good case to show how history and science can work side by side with different materials. And talking about material: what about Lesueur’s illustration? Well, ornithologists have confirmed it is quite incorrect because he mixed the three Dromaius species in one drawing that was supposed to show only one of them. I told you Lesueur was not a remarkable artist…

Bibliography:

Christian Jouanin, "Les emeus de l'expédition Baudin", L'Oiseau et la Revue Française d'Ornithologie, 29, 3, 1959, p. 168-201.

Nouveau dictionnaire d'histoire naturelle, appliquée aux arts, à l'agriculture, à l'économie rurale et domestique, à la médecine, etc, 10, 1817, p. 212.

Shane Parker, "The extinct Kangaroo Island Emu, a hitherto unrecognised species", Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club, 104, 1984, 19–22.

Stephane Pfennigwerth, “New Creatures Made Known: Some Animal Histories of the Baudin Expedition”, dans John West-Sooby, Discovery and Empire: the French in the South Seas, Adelaide: University of Adelaide Press, 2013, p. 171-214.

Baldwin Spencer, "The King Island Emu", The Victorian Naturalist, 23, 7, 1906, p. 139-140.

Voyage de découvertes aux terres australes, 2 vol., 2 atlas, Paris: Imprimerie impériale, 1807-1816.