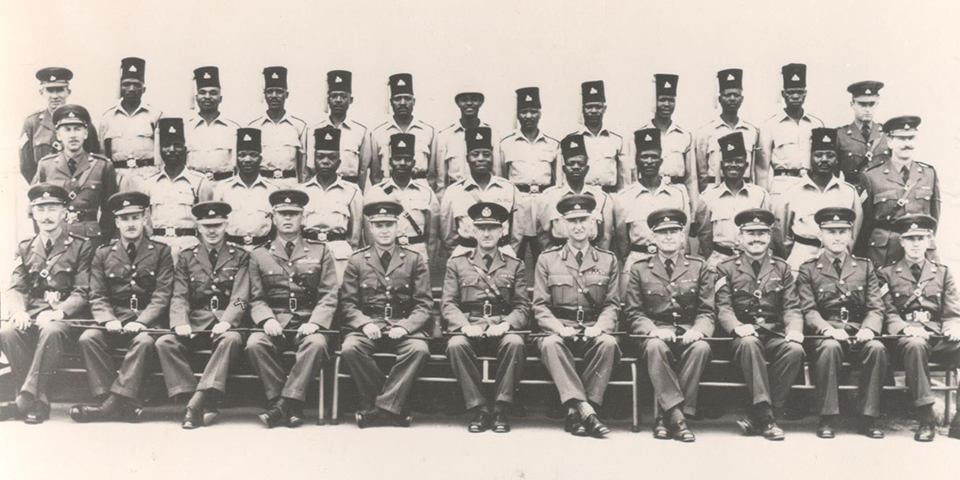

Brian Ngwenya

Order, Politics and Memory: African Police and State-Making in Zimbabwe, c1960-90

Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Julia Tischler

This historical study examines the different ways through which African police forces mediated the process of decolonization and the expansion of the nation-state in Zimbabwe between 1960-1990. Using Alltagsgeschichte as a methodological lens, I investigate African police “self-understandings” and their “situated subjectivities” as bureaucrats of the colonial and post-colonial states they served. By exploring the quotidian interactions of the supposed collaborators; between the structures and hierarchies of colonial and post-colonial states on one hand, and the broad sections of the colonial African society, on the other, I seek to understand how African police navigated and negotiated their lives and work vis-a-vis the particular ambiguities of decolonisation in a settler context. Consequently, I conceptualise African police as political actors whose personal motivations as well as their outlook on law and authority and visions of the nation-state have contributed to the formation of the nation-state in Zimbabwe. By placing African police at the centre of analysis, this study seeks to argue that this group of subjects shaped the process of decolonisation and the post-independence recasting of the nation-state in more complex and multifarious ways than existing research acknowledges.

Broadly, examining Zimbabwe’s violent and drawn-out decolonisation process through the lens of African police intermediaries contributes to historiography on colonial policing and everyday life in former settler colonial states. Trapped in the polarised binaries of collaboration and resistance, existing historical studies on the matter, whether written from the stand-point of empire or as institutional histories, have been preoccupied with the coercive nature of policing as central to controlling colonial societies and maintain the authority of alien rule. Neither of these perspectives left much room for systematically studying the socio-political histories of agents like police during the crises of decolonisation in Africa beyond common-place stereotypes. Secondly, by extending into the post-independence era, it not only makes critical empirical contributions to literature on intermediaries in the late colonial years but also stretches the category to new frontiers.

More specifically, the approach complicates several narratives in the historiography of African nationalism and decolonisation. Firstly, it allows us to re-think the binaries of collaboration and resistance, as well as domination. This can show the complex agency of state bureaucracies and their clients in the context of the colonial retreat and the making of the nation-state. This multiplicity of choice and action, I argue, is essential to understanding the micro-processes of decolonisation in former settler colonial state. In particular, I aim to demonstrate how individuals on the ground viewed emancipation, and the subtleties, ambiguities and ambivalences produced by the heterogeneity of thought and action. Interpreting decolonisation thus moves away from interpretations of liberation struggles that emphasize the bifurcation of winners and losers. Instead, we attain a nuanced analysis which draws out the multiplicity of stakes and shifting loyalties in a spectrum of political possibilities. Lastly, the study provides a useful foundation from which to comprehend both the complexities of law enforcement and the dynamics of history and memory in contemporary Zimbabwe and African politics.

The study will use material from various archival collections in UK, South Africa and Harare. In addition, oral interviews with retired African police and their immediate families will be used extensively in order to corroborate archival material. I shall also consult various such as newspapers, crime and court records, autobiographies, novels and memoirs.